Balancing the plate: Jimmy Smith opens ‘Private Sector Mechanism Partnerships Forum on Livestock’

The post was the keynote address “Balancing the Plate” by Jimmy Smith, Director General of the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI). This was delivered during the International Fund for Agricultural Research Luncheon on the ‘Zero Hunger Challenge’ for the Private-Sector Mechanism Partnerships Forum on Livestock, which took place 30 June 2016.

Will livestock help us address Agenda 2030, in particular the Zero Hunger Challenge?

I’m here to make the case that we have a golden and rare opportunity to ensure that livestock are viewed not as a problem to be fixed but as part of many solutions to many global problems. I’m going to argue that livestock are powerful, if as yet underused, instruments for leveraging the systemic changes we need both to end hunger and to create sustainable food systems globally.

Balancing the plate

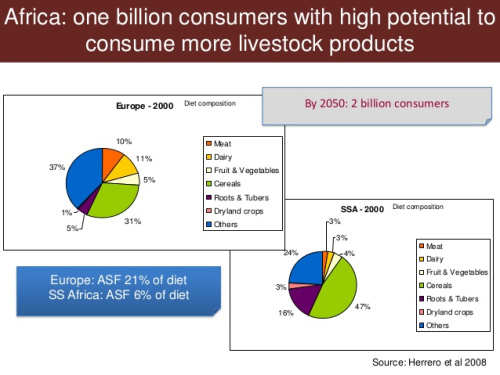

As we’ve just sat down to this fine meal, let’s start with how we can ‘balance the plate’. Can we manage to reduce the over-consumption of meat, eggs and dairy products that’s harming human health and the environment while also increasing under-consumption of these nutritionally dense foods by one billion of the world’s poorest people, thereby improving the nutrition and health of the latter?

In a word, yes.

I’m going to focus here on the big opportunity for the latter. As you know, one reason the livestock sector can play such a big role in sustainable development is that the skyrocketing demand for livestock products is taking place almost entirely in poor countries and emerging economies, where, of course, development of all kinds, particularly in meeting the ‘Zero Hunger Challenge’, remains paramount.

Let’s review the astonishing predictions of global livestock growth brought about by the rising populations, incomes and urbanization in poorer countries and emerging economies. This is where all the action is. In just 45 years, from 2005 to 2050, the world’s dairy requirement is expected to double, reaching almost 1 billion tonnes per year, with some 65% of that demand occurring in low- and middle-income countries. Demand for meat will also rise, nearly doubling from 258 to some 450 million tonnes each year, with over 70% of that demand occurring in these same developing and emerging economies. Demand for monogastric foods—pork, poultry meat and eggs—will rise at least four-fold, again mostly in developing countries.

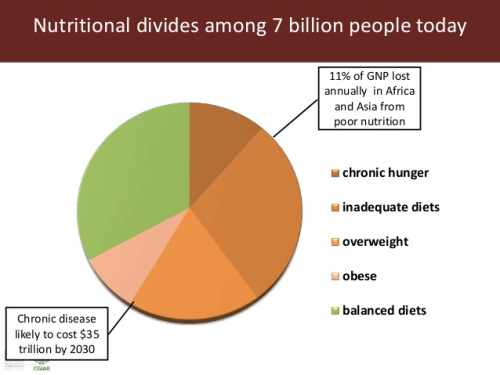

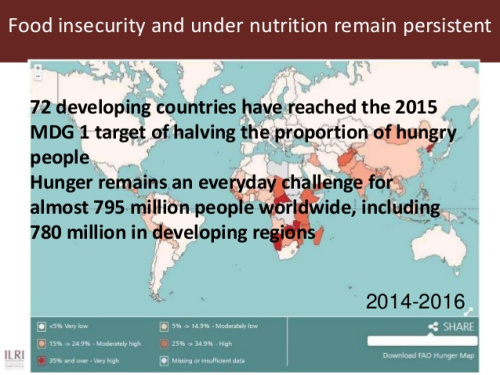

Large inequities, however, will remain. In spite of good progress in nutritional security in recent years, undernutrition today continues to reduce global GDP by a stunning US$1.4–2.1 trillion a year, stunting 159 million children (IFPRI 2016). And while total global demand for livestock will continue to rise, the per capita consumption of meat in low-income countries will continue to average just one-third that of consumption in the USA.

Balancing the messages

Thus, to bring about more balanced food plates, we’re going to have to do more than enhance small-scale livestock productivity. We’re going to have to also balance the public messages about this sector that so regularly become damning headlines in major media. We’re going to have to persuade Western publics and donors and decision-makers that while ‘livestock bads’ are real and must be addressed, and while the health and nourishment of all the world’s people matter, there is simply no moral equivalence between those who make poor food choices and those who have no food choices at all, between those who over-consume livestock-source foods and those who can afford no livestock-source foods at all.

This is not a zero-sum game. Sustainable development is a goal for all countries today, whether rich or poor, and whether service- or industrial- or agriculture-based. Today’s livestock researchers are delivering options for sustainable livestock systems of all kinds, operating in all circumstances and in all countries.

Balancing the partnerships

Let me now mention a third balance that we need to effect. This is arguably the most important. This is balanced partnerships—partnerships between publicly funded not-for-profit organizations such as my mine and the private for-profit companies in livestock, agricultural and related fields such as those represented in this room.

With the market value of Africa’s animal-source foods in 2050 estimated at USD151 billion, it will not have escaped those of you representing the private sector that the on-going livestock revolution in Africa and other regions of the developing world presents significant opportunities for private-sector investment, whether that be (first opportunity) investing in production of livestock products in Europe, North America or Australasia for export to Africa and Asia or (second opportunity) investing in new ventures to establish major livestock production units in the developing regions.

Perhaps an even greater investment opportunity for the private sector is the provision of livestock inputs and services for the plethora of small- to medium-scale livestock operations that characterize livestock systems in today’s developing and emerging economies. This would not only meet a significant market need but also enable livestock enterprises to become a major player in meeting the Sustainable Development Goals. This (third opportunity) is the opportunity to begin partnering with the nearly one billion smallholders whose livelihoods—as well as income, food, jobs, fertilizer, traction and insurance—depend on livestock.

Not all of today’s livestock smallholders will become efficient, market-linked producers or involve themselves in processing and trading animal products. Many will leave the sector altogether. Over time, it’s expected that most of today’s smallholders will be replaced by larger, more efficient livestock operations (with transitions in poultry and pig units occurring faster than those in the dairy sector). These millions of people and livestock systems in big transition over the coming decades offer companies business opportunities not to be missed.

Meeting the growing demand of the growing developing-world’s populations for meat, milk and eggs will require big on-going changes in how today’s smallholders produce and market their livestock products. The private sector can help guide these transitions so that they not only become profitable for all but also serve to enhance livelihoods and food and nutritional security; to ensure food is safe to consume; to provide employment for women, youth and other unskilled labour; and to protect the natural resource base.

About a third of today’s smallholders are already in the process of commercializing their livestock operations, which means they’re already customers for the right private-sector inputs and services. Another third may live in regions too distant from markets to take advantage of private-sector services, although there are exceptions, which I’ll get to in a minute. The last third of today’s smallholders could move in either of these two directions, becoming commercially viable livestock producers or exiting the livestock sector altogether. For this last group, public investments will be key in helping people shift their production systems from subsistence- to market-oriented, whereupon, of course, they would likely become customers of appropriate private-sector inputs and services.

What the public sector offers the private sector are the initial research and development investments, such as the development of new vaccines or diagnostics, that lay the groundwork for further investment and engagement by private companies. Working together productively and efficiently, public-private partnerships can pay off handsomely, helping next-generation livestock entrepreneurs build and expand vibrant local, regional and international markets. Such public-private partnerships can provide the company’s stakeholders with a profitable bottom line while also fulfilling on the company’s social corporate responsibility and the public organization’s ‘public good’ mandate.

I must now include a caveat, which is that the small-scale livestock systems so ubiquitous in the developing world are very different ‘beasts’ from the large-scale livestock operations private companies are accustomed to dealing with in the developed world and in the emerging economies of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa. Agricultural business models employed today in the North cannot be directly transferred to the South. New business models suiting smallholders need to be jointly innovated, tested, refined and applied. Working together and combining our different areas of expertise, those of us in local, public and private organizations have the chance to build new models of great practical use by smallholders ambitious to build viable livestock businesses. At the same time, we also have the chance to help steer the fast-evolving smallholder livestock systems of developing countries in healthy, equitable and sustainable directions.

Examples of public-private-partnerships at ILRI

How specifically can the private sector help bring this about? Let me end by telling you of a few of the ways we’re working with the private sector at ILRI.

Livestock vaccines

ILRI is working with Harris Vaccines Inc to test its proprietary vaccine technology for East Coast fever and with Senova GmbH to develop a lateral flow diagnostic test for contagious bovine pleuro-pneumonia. We’re working with Hester Biosciences Ltd to improve development of a thermostable vaccine against peste des petits ruminants. This veterinary vaccine company with R&D units, production sites, distributors and diagnostic labs in India is interested in developing Africa as a market for small-scale poultry and other livestock vaccines. New livestock vaccines should help reduce the need for drug treatments, whose mis- or overuse is leading to antimicrobial resistance. Disease reduces global livestock productivity by 25%—valued at USD300 billion per year—and costs Africa USD9–35 billion per year. ILRI has estimated that an annual global investment of USD25 billion in One Health approaches could save as much as USD100 billion annually in disease costs.

Livestock feeds

Production and sales of combined and processed feeds is emerging as a small- to medium-scale industry in some parts of the developing world, such as in India, where smallholder producers dominate the dairy sector. Better livestock feeding not only improves the productivity of livestock but also reduces the amount of greenhouse gases livestock emit as they digest their feed. ILRI has worked with the animal feed company Novus International to develop livestock feed supplements (starter pellets and molasses blocks) designed specifically for use by African smallholders. We’re working with the Kenya Cereal Millers Association, which has over ten million customers, to reduce the risk of Kenya’s consumers to exposure to high levels of carcinogenic aflatoxins in maize flour; a related group is investigating the use of contaminated cereals as livestock feeds.

Livestock insurance

We’re working with private insurance and reassurance companies to provide index-based livestock insurance to poor and never-before-insured remote livestock herders in Africa to protect them against catastrophic drought. Because insuring animals moving across vast landscapes is impossible, the team uses satellite data to assess the health of rangeland vegetation. When feed availability falls below a certain level, it triggers an insurance pay out. Insurance policies can be bought for any number of animals. Aid agencies can invest in (or subsidize) this insurance rather than investing in more costly and unpredictable emergency responses to severe drought. Preliminary results indicate that those insured were less likely to sell their animals in distress sales (36%), to reduce their meal intakes (25%) and to depend on food aid (33%).

Conclusions

At my institute, we’ve found that working closely with people and organizations with very different mindsets and modus operandi, while often challenging, can also be highly productive and rewarding. Having to learn the language of different organizations, and to modify our thinking and behaviour accordingly, has stretched us, encouraged us to think big and outside the box, to take risks we wouldn’t normally take.

The huge appetite growing in the developing world for meat, dairy and eggs is unprecedented; it’s not going to remain ignored for long by the private sector. Where there is such growth, private companies will jump in. I’ve said that this moment offers companies great opportunities to extend their markets, often accompanied by opportunities to fulfil their corporate social responsibilities. I’ve argued that by working together, private, public and civil society organizations can help rebalance global livestock diets, global views of livestock and global livestock partnerships. I invite all of us in this room to work together to find better ways of serving the world’s pastoralists, commercial grazers, mixed crop-livestock farmers and intensive livestock producers, ensuring that they are not left behind, but become part of the world’s sustainable as well as profitable livestock futures.

So, can we achieve balance? Can we meet the demand for animal-source foods while addressing Agenda 2030? Yes, I believe we can. We have a unique opportunity to grasp right now. Can the private sector do this alone? No. Can we do this without the private sector? No. This kind of accomplishment can be achieved only by making the (collective) whole greater than the sum of the (individual) parts. And to manage that, we’re going to need all the balanced food plates, messages and partnerships we can get.

Thank you for your kind attention.